Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine

Warning

No one should be self-administering these or any other experimental treatments for COVID-19.

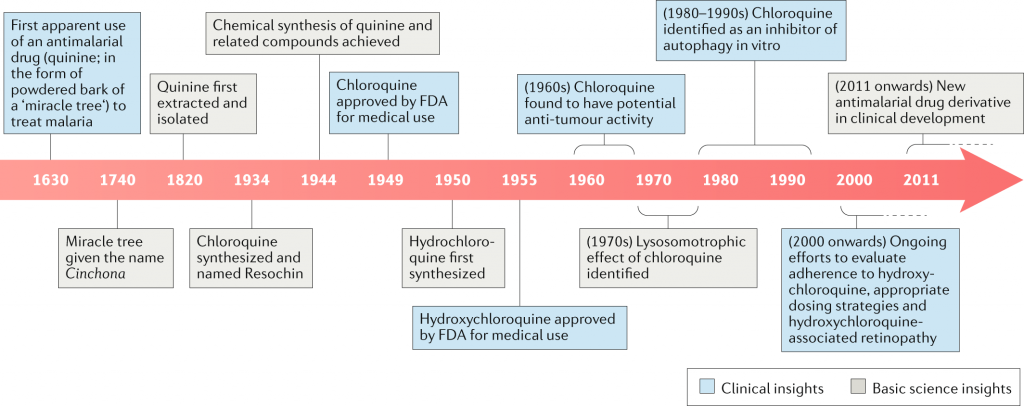

Bayer invented the antiviral medicine chloroquine in 1934, and it has been used for decades to treat malaria throughout the world. Hydroxychloroquine was invented during World War II to provide an alternative with fewer side effects.

New York Times report study halted over risk of fatal heart complications

A research trial of coronavirus patients taking higher dose of chloroquine was stopped in Brazil after patients developed irregular heart rates.

Packets of Nivaquine tablets containing chloroquine, and Plaquenil tablets containing hydroxychloroquine. Drugs making headlines as a coronavirus treatment.

Credit…Gerard Julien/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

The Brazilian Study

A small study in Brazil was halted early for safety reasons after coronavirus patients taking a higher dose of chloroquine developed irregular heart rates that increased their risk of a potentially fatal heart arrhythmia.

Chloroquine recently received alot of attention when the US President has enthusiastically promoted them as a potential treatment for the novel coronavirus despite little evidence that they work, and despite concerns from some of his top health officials. Last month, the Food and Drug Administration granted emergency approval to allow hospitals to use chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine from the national stockpile if clinical trials were not feasible. Companies that manufacture both drugs are ramping up production.

Doctors recommend screening with an electrocardiogram to prevent the drug from being given to the 1 percent of patients at the greatest risk of a cardiac event. The drugs also cause serious adverse effects such as acute psychoses have been reported following treatment with chloroquine. Chloroquine can cause cell death, including neurons. It can also cause cause vision loss called retinopathy with long-term use.

The Brazilian study involved 81 hospitalized patients in the city of Manaus and was sponsored by the Brazilian state of Amazonas. It was posted on Saturday at medRxiv, an online server for medical articles, before undergoing peer review by other researchers. Because Brazil’s national guidelines recommend the use of chloroquine in coronavirus patients, the researchers said including a placebo in their trial — considered the best way to evaluate a drug — was an “impossibility.”

Despite its limitations, infectious disease doctors and drug safety experts said the study provided further evidence that chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, which are both used to treat malaria, can pose significant harm to some patients, specifically the risk of a fatal heart arrhythmia. Patients in the trial were also given the antibiotic azithromycin, which carries the same heart risk. Hospitals in the United States are also using azithromycin to treat coronavirus patients, often in combination with hydroxychloroquine.

The study conveys one useful piece of information, which is that chloroquine causes a dose-dependent increase in an abnormality in the ECG that could predispose people to sudden cardiac death,” said Dr. David Juurlink, an internist and the head of the division of clinical pharmacology at the University of Toronto, referring to an electrocardiogram, which reads the heart’s electrical activity.

Roughly half the study participants were given a dose of 450 milligrams of chloroquine twice daily for five days, while the rest were prescribed a higher dose of 600 milligrams for 10 days. Within three days, researchers started noticing heart arrhythmias in patients taking the higher dose. By the sixth day of treatment, 11 patients had died, leading to an immediate end to the high-dose segment of the trial.

The researchers said the study did not have enough patients in the lower-dose portion of the trial to conclude if chloroquine was effective in patients with severe disease. More studies evaluating the drug earlier in the course of the disease are “urgently needed,” the researchers said.

Several clinical trials for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are testing low doses for shorter periods of time in coronavirus patients. But the Health Commission of Guangdong Province in China had initially recommended those sick with the virus be treated with 500 milligrams of chloroquine twice daily for 10 days.

One of the authors of the Brazilian study, Dr. Marcus Lacerda, said in an email that his study found that “the high dosage that the Chinese were using is very toxic and kills more patients.” “He went on to say that it is for this reason this arm of the study was halted early,” he said, adding that the manuscript was being reviewed by the journal Lancet Global Health.

Dr. Bushra Mina, the section chief of pulmonary medicine at Lenox Hill Hospital in Manhattan, said the study would most likely not change his hospital’s practice of giving a five-day course of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin to hospitalized patients who were not severely ill. Dr. Mina said patients are monitored daily for heart abnormalities and the drugs are stopped if any are found.

New Study – The National Institutes of Health (NIH)

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced Thursday that it’s begun enrolling participants in a clinical trial to test the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine in treating COVID-19. The Hill reports:The first participants have enrolled in the trial at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn. The study will be conducted by the NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. According to the NIH, the blinded, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial aims to enroll more than 500 adults who are currently hospitalized with COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, or who are in an emergency department with anticipated hospitalization.

Participants will be randomly assigned to receive 400 mg of hydroxychloroquine twice daily for two doses (day one), then 200 mg twice daily for the subsequent eight doses (days two through five) or a placebo twice daily for five days. Hydroxychloroquine is used to treat malaria, lupus and rheumatoid conditions such as arthritis. However, its effectiveness at treating COVID-19 has never been proven, despite its embrace by President Trump. The evidence on hydroxychloroquine is conflicting, at best. NIH scientists said urgent clinical evidence is needed. Even so, the study is not estimated to be completed until July 2021.

Conclusion

There is clearly no evidence that the drugs work against the coronavirus, despite their use by hospitals and doctors in the United States and other countries since the outbreak began. Their antiviral properties have been proved in test tubes, but rigorous clinical trials to test their effectiveness in humans have not been completed. The repetitive statement made by experts not pushing drugs money is “if you’re going to use it because you have no alternative, then use it cautiously!”

References

- Science Direct. Psychosis following chloroquine ingestion: a 10-year comparative study from a malaria-hyperendemic district of India

- The American Academy of Ophthalmology. Recommendations on Screening for Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy – 2016

- The National Institutes of Health